Barbenheimer – what started out as an internet joke grew into some else entirely – a massive cultural and marketing sensation. The two films, which will be forever linked by their same-day release dates, are diametrically opposed in genre, style, tone, and aesthetic – resulting in possibly the most disparate double bill in history. However, there are a striking number of similarities between the two tentpoles.

They are both massively ambitious, written and directed by two of the most esteemed filmmakers working in Hollywood who have Oscar nominations not just for their directing, but their screenwriting. Oppenheimer and Barbie are both passion projects led by husband-and-wife-founded production companies with the backing of a major studio. They are led by all-star casts in front of the camera, and accomplished crews behind the scenes, all working together in perfect harmony to deliver a visual feast of exquisite production design, cinematography, costumes, and special effects about two of the most influential figures in history – Oppenheimer and Barbie.

During a year when there was a new Fast & Furious, Little Mermaid, Spider-Man, Transformers, Indiana Jones, and Mission: Impossible movie, along with Michael Keaton coming back to play Batman again in The Flash after 31 years, the biggest cinematic event of the year is Barbenheimer – two original screenplays helmed by critically acclaimed directors. These are the broad strokes that connect Christopher Nolan’s harrowing biopic focused on the father of the atomic bomb, and Greta Gerwig’s romp based on the Mattel fashion dolls, which also happen to tackle similar questions involving existentialism, identity, legacy, and complicity with equal vigor. But the question is, do they deliver?

Oppenheimer is a story told singularly across eleven miles of 65mm film by one of the singular storytellers working today. Nolan has shot specifically for IMAX before, but with Oppenheimer, he revolutionizes the large format once again. In lieu of the traditional action of a Dunkirk, the director uses IMAX’s expanded aspect ratio and crystal clear imaging to allow the audience to access Oppenheimer’s thought process and peer into his soul. Cillian Murphy’s haunted stares, which carry the curse of prophetic power, are shot up close and personal, capturing every detail of his cavernous cheekbones and piercing blue eyes.

In the first five minutes, Ludwig Göransson’s blaring score blows you away and fills you with a sense of creativity, exploration, wonder, passion, and awe – accentuated by frenetic flashes of atomic particles swirling, smashing, and sparking in Oppenheimer’s mind. This immediately conveys how imaginative and intense he is, but also troubled when he attempts to poison his demanding physics tutor with a cyanide-laced apple. Oppenheimer is a brilliant physicist but with the temperament of a temperamental artist and polyglot poet who gets off on reading the Bhagavad Gita in Sanskrit during sex.

Though Oppenheimer is about way more than the bomb, the movie is most captivating during the Manhattan Project portion as some of the world’s top scientists race to build the world’s first weapons of mass destruction before the Nazis do. This staggering suspense intensifies during the Trinity Test and reaches an apex leading up to the moment of detonation, amidst uncertainty it might start an unstoppable chain reaction that could destroy the world. The atomic blast itself, which was created entirely without CGI, is awe-inspiring, mesmerizing, hypnotic, dangerous, and simply extraordinary.

Oppenheimer’s ambitious structure is unrelenting and fittingly, for a film about the man who named the first nuclear-bomb test “Trinity” inspired by the poetry of John Donne, it’s essentially three expertly intertwined segments focusing on Oppenheimer the academic, the scientist, and the politician. The film skips around and splices different moments of time in a purposefully disorienting fashion, which has become one of the director’s defining features, though while Dunkirk was incredibly economical, Oppenheimer runs 3-hours long, and like Memento, it’s told through a combination of color and black-and-white.

The color scenes, which Nolan says represent Oppenheimer’s subjective point of view, are prefaced as “fission,” which is when something is split into two or more parts. In the case of the Manhattan Project, multiple nuclei of uranium are being split simultaneously, resulting in the huge energy output of an atomic bomb. Similar to the chain reactions seen in nuclear fission, which was still a relatively new theory at the time, this is what Oppenheimer himself represents. He chose to come back to America after years of studying abroad because he wanted to be a catalyst in the nascent field of quantum mechanics. Oppenheimer was essentially envisioning another plane of existence, though he largely failed to foresee its full ramifications, like the ripples caused by raindrops in a pond.

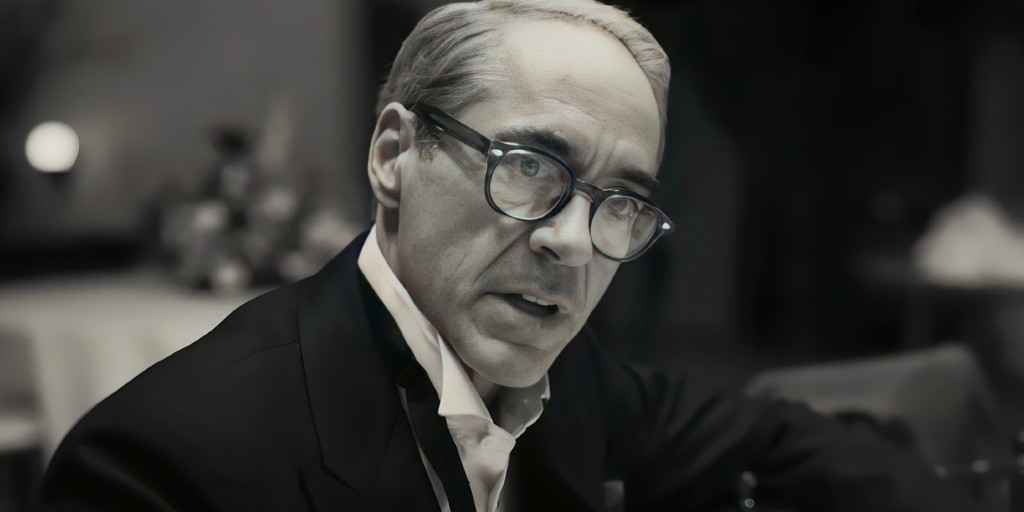

The black-and-white scenes, which Nolan says represent the more objective point of view of Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.) are labeled fusion – the combining of two or more parts into a larger particle, This is the process used by the hydrogen bomb, as proposed by Benny Safdie’s Edward Teller, and is an exponentially greater energy output compared to fission. These later black-and-white scenes have been criticized for paling in comparison to the greatness of the Manhattan Project portion, though they are necessary to depict the devastating consequences of the atomic bomb, which Oppenheimer thought would end all wars. Instead, the ripple effects caused the Cold War, McCarthyism, and the campaign to discredit Oppenheimer for advocating against the hydrogen bomb.

Nolan’s three-hour historical biopic is dense like a Wikipedia article and moves at a breakneck pace to boot, but for one extremely unsettling scene, Oppenheimer fully transforms into a full-blown horror film. Haunted by immense death and destruction caused by the bomb, Oppenheimer attempts to deliver a rousing speech in a gymnasium to the sound of stomping feet, blood-curdling screams, sudden silence, blinding white light, and incinerating bodies dissipating into dust, all capped off by Oppenheimer stepping on a charcoaled corpse. Oppenheimer’s greatest fear, however, is that he started a chain reaction that will destroy the world, and the movie’s brilliantly haunting ending, which is one of the best in recent memory, suggests that he did.

With Oppenheimer, which feels like a culmination of his filmography, Nolan successfully mines one of the greatest dramatic stories in history for an epic thriller that thrusts audiences into the pulse-pounding paradox of the enigmatic man who risked destroying the world in order to save it. It’s an extraordinary experience that leaves you with resonances that will want you to revisit again, again, and again.

Oppenheimer absolutely delivers, and it could easily be one of the best films of the decade. 10/10

Barbie begins with a direct parody of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey complete with “Also Sprach Zarathustra,” and from the opening scene, Gerwig completely shatters expectations of a Barbie movie starring Margot Robbie. As its lead star says, “People immediately have an idea of, Oh, Margot is playing Barbie, I know what that is, but our goal is to be like, Whatever you’re thinking, we’re going to give you something totally different — the thing you didn’t know you wanted.”

After a long choreographed dance sequence set to Dua Lupa’s diegetic “Dance the Night Away,” Margot Robbie’s flawless heroine blurts out an intrusive thought, “Do you guys ever think about dying?” that brings her blowout party to a screeching halt: It’s a hilarious non-sequitur, especially after three hours of Oppenheimer mulling death and destruction, that sets up Barbie as an existential exegesis made under the aegis of its manufacturer Mattel, which sometimes overshadows its own pointed critique of the patriarchy, perfectionism, and misogyny. Otherwise, Barbie functions just fine as a search for self-discovery.

Gerwig’s fun feminist fable, while cleverly satirical, is largely overshadowed by the sheer scale and importance of Oppenheimer, with Nolan calling its subject “the most important person who ever lived,” or as Matt Damon’s General Leslie Groves puts it more excitedly, the Manhattan Project is “the most important fucking thing to ever happen in the history of the world!”

With Barbie, Gerwig and her creative and romantic partner Noah Baumbach pull off the impossible juggling act of delivering a family-friendly fantasy that soft-peddles satire while simultaneously paying homage to and making a socially aware statement about the Barbie brand. As Gerwig says, “Things can be both/and. I’m doing the thing and subverting the thing.”

Barbie’s existential journey is comparable to Oppenheimer’s, an American Prometheus who stole fire from the gods and gave it to man, and for this, he was chained to a rock and tortured for eternity, though other versions of the Greek myth credit Prometheus with the creation of humanity. Barbie meets her own creator, Barbara Handler, and must choose whether to remain an immortal creation in the idyllic confines of her artificial existence or become human in the real world, despite all its discomforts like aging and death. This emotional moment is set to the melancholic yet mellifluous sound of Billie Eilish’s “What Was I Made For?”

Barbie delivers on being a visually dazzling comedy, but also a deconstruction of the doll itself. 8/10

United in cinematic history due to their same-day release date, Barbie and Oppenheimer also seem like, by sheer coincidence, Nolan and Gerwig’s attempts to grapple with existential dread in their own ways. Barbenheimer, the biggest cinematic event of the year is, surprisingly, two genuine character studies that, while not short on spectacle, are ultimately about the existential horror of being alive.